“Nobody sees a flower — really — it is so small — we haven't time — and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.” — Georgia O’Keefe

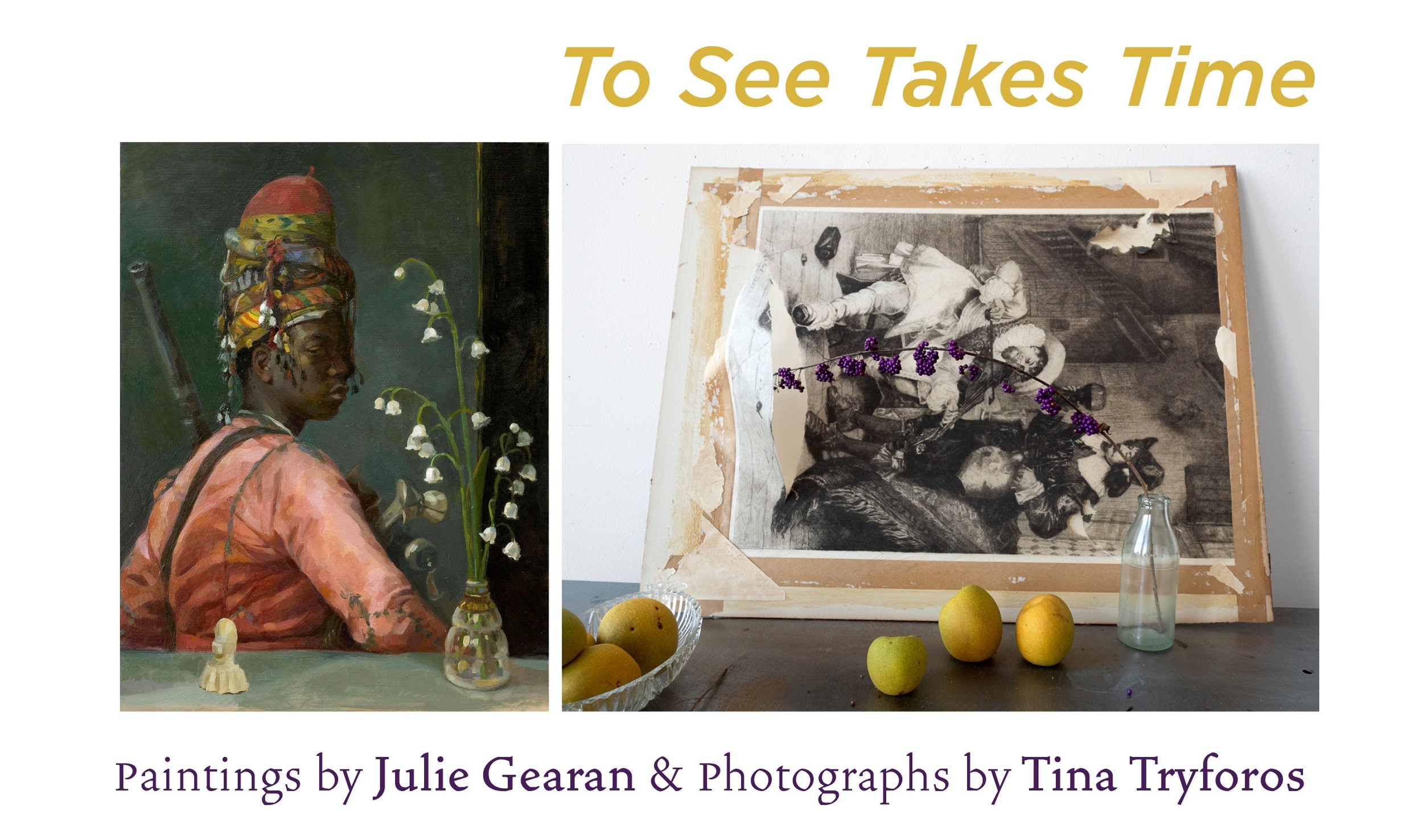

Through our friendship, we have survived the loss of parents, cancer, our 40s, and motherhood. We are a painter and a photographer, and as friends we talk a lot about nurturing art-making and reconciling it with life; how the creative drive draws from our personal narratives, our communal histories, and the uncertainty of current events.

Covid flowers begged to be looked at. They were bolder and brighter last spring, weren’t they? Or were our eyes just hungrier to behold that symbol of persistent life? While we were washing our groceries and stitching homemade masks, the roses were sucking up scant nutrients from the soil as always and bloomed in complete contrast to our feelings. Joyous, giant blossoms.

Flowers are metaphors for life and death. They memorialize deep personal and communal loss, and celebrate milestones. Flowers appear in mythology, art history, and poetry, tethering the past to the present. They serve as weighty symbols while being ephemeral.

But to “use” them in service of art? Cheap. Redundant.

They were gifts. Offerings. Let them be in the liminal space. Let them be.

And then, they had a recipient. A reason for their boldness. Fecundity.

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, which loudly echoed the multitude of unjust deaths of Black Americans, it was clear: These blossoms were in memoriam. Again. Still.

Together there is cross-pollination and shared struggle. There is wonder in interpreting flowers, as well as a constant awareness of their death — their delicate lives reflect an unease about our own. We are women making and showing flower pictures to reclaim the genre.